PHILADELPHIA, Pa. USA — There apparently weren’t enough Mary Cassatt paintings in Paris, so I came to America to get my fill of one of my favorite American expats, a single lady from Pennsylvania who abandoned her native land for France.

We have some things in common. Much of my family on my dad’s side came from the Keystone State. They were German immigrants to Lancaster County, PA, who later farmed the land in the state’s northwest. My grandfather joined the national guard and fought in the northeast of France during the “Great War” .

Mary Cassatt’s Pennsylvania life began in Allegheny County, near Pittsburgh, where her father was a well-to-do stockbroker and land speculator. The family migrated to Lancaster County and then Philadelphia, where Mary (one of seven Cassatt kids) studied art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in the mid 19th century.

Lest we all forget, America was no prize in the mid-19th century. It was at war with itself over slavery, its medical care was barbaric, politicians physically attacked each other in Congress and women were the chattel of their fathers, husbands, brothers and any other man their male overseers decided would offer the best price.

They were limited to very few professions, hardly any of them, save teacher or governess, respectable. Being an “old maid,” a “spinster” or an over-educated “bluestocking” earned women pity and scorn. To have status meant getting married, losing all you possessed to your mate and risking your life to the primitive and barbaric health care that bled the sick and used leeches to suck the leftovers.

America’s chronically religious government deemed contraception and anaesthesia for laboring women to be against their God’s will. Women often died giving birth. Suffering was a woman’s job. Society made sure it was mandatory.

Mary wasn’t interested.

She wanted to paint, she fairly “itched” to paint, she wrote. But her training in Philadelphia was constrained by the limits 18th century society imposed on women: The male artists and teachers were patronizing and dismissive, she couldn’t draw the nude figures her fellow male students used and her world was small and confined by strict social rules (think the Taliban and crinoline instead of burkas.)

)

Painting and exhibiting with men wasn’t what nice girls did. Mary and her well-educated family eventually did what well-educated folk of the day did – they traveled. First they landed in Germany, where Mary learned German and painted. They moved on to France, where she took up French and began exploring the world’s most beautiful city, where women could actually go out in the evening for an ice cream and drive their own carriages on the wide boulevards.

America became a distant memory. The Académie des Beaux Arts didn’t yet admit women, but Cassatt could study with its teachers and join other women copyists who toiled in the Louvre to reproduce the works of the masters. She got her first painting accepted by the Paris Salon (the exhibition venue for the académie) in 1868, but her father hustled the family back to America in 1870. He wasn’t a fan of his daughter’s penchant for work instead of settling down to domestic “bliss.”

Mary tried working in America, but found little encouragement or acceptance in a country dominated by religious fanaticism and misogyny. She beat a hasty retreat to Paris after being cut off from art study when her father stopped funding it.

Her career advanced after she settled back into French life. Despite rejections, she pushed on and befriended the rebel group of impressionists, including its only other female member, Berthe Morisot. Initially scorned and rejected, the impressionists soon became a formidable force in the Paris art world.

Mary Cassatt was its only American member.

The rest of her American family soon arrived in France and she lived with them. It likely wasn’t always happily, but Mary Cassatt earned respect for her talent, her mastery of printmaking and her unique choice of subjects, the surroundings of her life: Mostly women and children.

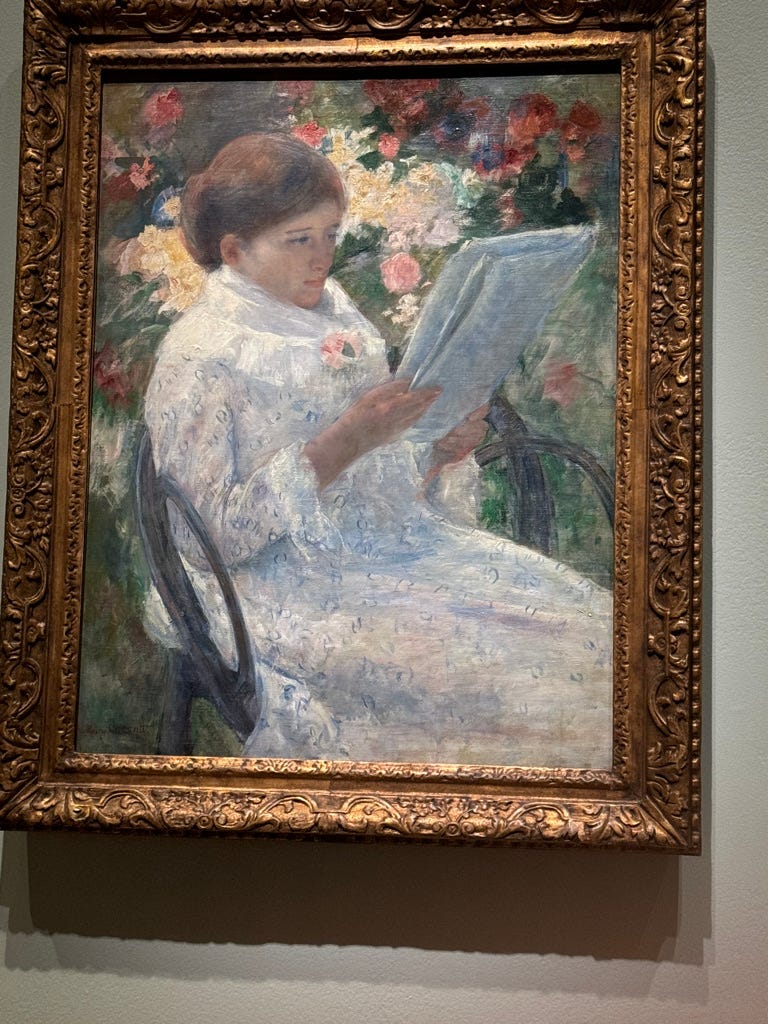

Last year I got a good look at Mary’s work in an exhibit in Giverny and at the Musée d’Orsay and the more I saw of it, the more curious I became about her view of the world and her place in it. The current show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art does an interesting job examining not only her technical innovations in different mediums, but her unique (for the time) vision of women’s life, work and passion.

As one of my companions observed at the exhibit this week: She painted women doing things she never did. She was a voyeur of the lives of her brothers and sisters, their babies and their domestic life. She wasn’t much of a participant.

Does this mean she disdained the roles her sisters and mother adopted? Was she being critical of their insular lives, mundane chores and the minutia of their interests?

I don’t think so. She paints these tasks with reverence, delicacy, affection and tenderness. I think Mary, like many women of the 21st century, felt the pull of marriage and motherhood, if only to please her circle of family and friends

I don’t believe Cassatt’s preoccupation with women and babies was just because they were familiar. Her artistic voice tells us she was rather sentimental about the relationships of parents and children. She was nostalgic for that path, if only, perhaps, to be socially acceptable. She loved being an artist, and she loved babies and family.

As many of my fellow baby boomer women can attest, balancing a career that appeals to your interests and education often conflicts with your desire to have a partner and to bear children. Being good at both isn’t often possible and feeling guilty about it is a certainty. Few women have male partners who are eager to change a merde-filled diaper, wrestle a wet baby in a bath or nurse infants at their breasts until they bleed.

Mary Cassatt knew that to be truly superior at your work outside of the home called for extraordinary devotion, preoccupation and time. With only 24 hours in a day, something had to give. In her case, it was being a wife and a mother.

She also knew how critical others can be of women who avoid domestic life. Family and friends can be disdainful and distrustful of women who take a path that leads them away from home. Mary Cassatt’s journey away from America and away from traditional women’s work may have earned her the sting of disapproval and censure from conventional society.

Her legacy to us is amazing and memorable work. The price she paid was a home life that made her an observer of what she could have had. The question for several of us who saw the show together in Philadelphia: Did she think her choice was worth it?

I think she did. Encouraged by her intelligent, well-read mother, Mary Cassatt understood she had a choice. She couldn’t have everything, either in America or France. She chose to work in France because America’s restrictive rules for women were more limiting than those of French society.

Still, she was keenly aware of what she had missed. Painting it gave her a connection to what might have been. Ruminating on what you might have missed is, in a sense, an homage, a meditation. Most of us know that there’s sporadic bliss in caring for a family. There’s also sporadic bliss in a career. Mary chose the latter, but I think she may have always wondered how the other life might have turned out.

Her paintings tell us what she imagined.